Without any serious opposition, I think I can say that Shel Silverstein is one of the most well-known poets of modernity. Whether it’s been a decade(s) since you flipped through his volumes with sticky fingers, giggling with your friends as a kid or you still relax with his antics before bed after a long day, Silverstein remains recognized foremost as a poet whose material often caters to children. As his poetry collections show, he’s a rather proficient cartoonist as well.

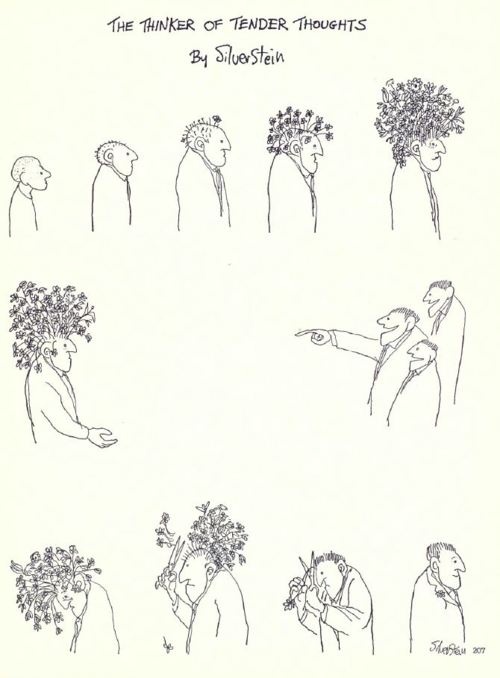

This leads me to the ambiguous nature of Silverstein’s work “The Thinker of Tender Thoughts” (as seen above). Aside from a title, the work is entirely composed of drawn images. What makes this more than just a “drawing” is the fact that these images are depicting action or a narrative, so we can agree that their sequential positioning is important to the whole. On their own, these figures don’t posses meaning, at least not the meaning that Silverstein is attempting to portray.

The piece lacks any formal “panels,” but this “action-to-action” progression of “icons” is very relatable to the medium of comics (here I used Scott McCloud‘s comic vocabulary). As I noted, there is a narrative that unfolds when the viewer follows the standardized left-to-right up-to-down pattern recognized by English speakers. This isn’t a requirement of a comic but a sense of progression and inter-connectedness between the images is.

Here’s where I think the implications get interesting. Comics and graphic novels have carried a very dark stigma in culture, particularly in that of the Western world. They’re seen as childish and dorky, something to be outgrown. Silverstein’s work is primarily thought of as being directed towards children, so his use of cartooning and this comic seems to fit the stereotype, right? Yet I can’t help but look at “The Thinker of Tender Thoughts” and feel like I relate to it infinitely more than I ever could have as a child. It details a man who changes himself to fit in after being ridiculed by peers, which we can all surely relate to at all ages (particularly in youth when peer pressure is said to be at its highest). But if this was truly written for a child, wouldn’t it be expected to teach them to embrace their uniqueness and not be a blind follower? No higher form of morality is offered, and in fact the man is smiling for the first time at the very end after he has conformed.

It’s a rather hopeless ending.